Some Assembly Required

The Truth (Ahem!) Behind the First Assembly Line

“If I Have Seen Further, it is by Standing Upon the Shoulders of Giants” Sir Isaac Newton

The notion of organized systems is ages old with brilliant examples across history.

Adam Smith discussed the division of labor in the manufacture of pins at length in his book The Wealth of Nations published in 1776, apparently a banner year for Americans.

The Venetian Arsenal, a complex of former shipyards and armories clustered together in the city of Venice, dating back to circa 1104, operated similar to a production line. Ships moved down a canal and were fitted by the various shops they passed. At the peak of its efficiency in the early 16th century, the Arsenal employed some 16,000 people producing one ship each day, and could fit out, arm, and provision a newly built galley with standardized parts on an assembly-line basis. Although the Arsenal lasted until the early Industrial Revolution, production line methods did not become common even then.

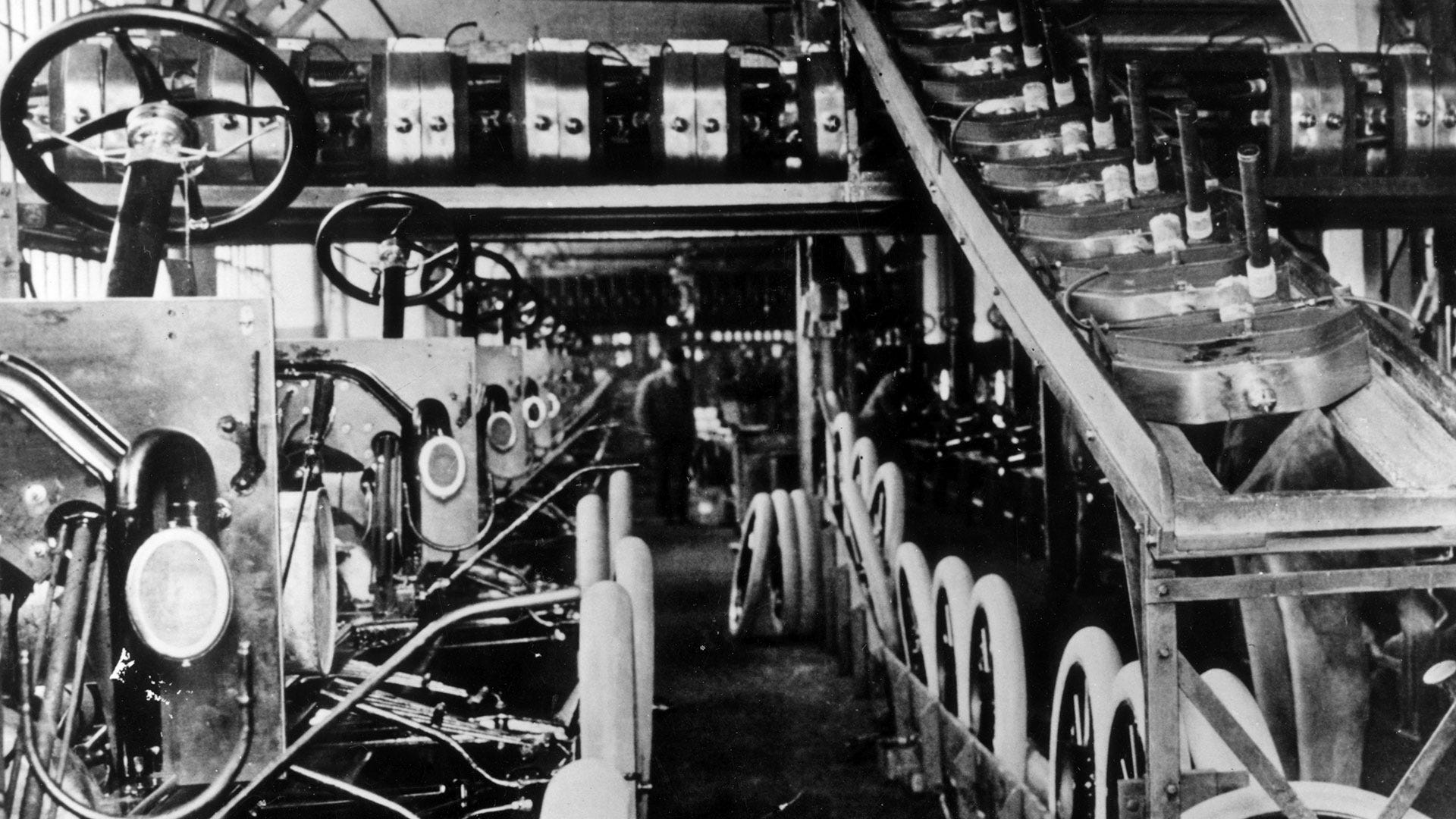

The architect of the modern assembly line was the Dane, Charles Sorensen, Ford’s production chief for 40 years. His experiments changed the face of manufacturing. Sorensen’s revolutionary idea of moving a vehicle past various workstations, with one worker performing a specific assembly task, transformed the neophyte auto industry and helped Ford dominate the marketplace for years. Ford nicknamed Sorensen “Cast-Iron Charlie.”

“Henry Ford is generally regarded as the father of mass production,” Sorensen wrote in his autobiography, My Forty Years with Ford, which was published in 1956. “Henry Ford had no ideas on mass production. In later years, he was glorified as the originator of the mass production idea. Far from it, he just grew into it, like the rest of us. The essential tools and the final assembly line with its many integrated feeders resulted from an organization, which was continually experimenting and improvising to get better production.

Ford and his managers were searching for new ways to increase production speed to keep up with consumer demand. They decided that the best way to achieve higher production volume was to change the way assemblers worked.

On April 1, 1913, the first moving assembly line for a large-scale manufacturing application began to operate. It was used to produce flywheel magnetos. The magneto coil was a key part of the Model T’s revolutionary ignition system. Instead of using dry batteries, as commonly used at the time, the vehicle featured a magneto that produced sparks for the cylinders, which made it much easier to start the engine. It consisted of a heavy flywheel with copper coils and 16 V-shaped permanent magnets bolted on its front side.

Traditionally, operators stood at individual workbenches and assembled an entire flywheel magneto. One person could build approximately 35 units in a 9-hour shift, or one every 20 minutes. However, by dividing the job into 29 separate tasks performed by 29 operators standing side by side, Sorensen and his team of engineers shaved 7 minutes off each final assembly. The operators were strategically placed along a waist-high row of flywheels that rested on smooth, sliding surfaces on a pipe frame. However, all did not adapt to the new system as workers produced at varying speeds. Sorensen solved this problem by setting the pace of production. He moved the magnetos down the assembly line with a chain and experimented with various speeds.

At first, the chain moved 5 fpm, which proved to be much too fast. Then 18 inches per minute was tried, but it was deemed too slow. Eventually, the assembly line moved 44 inches per minute.

By raising the height of the assembly line, moving the magnetos with a continuous chain, and lowering the number of operators to 14, Sorensen and his engineering team achieved an output of 1,335 flywheel magnetos, which translated into 5 minutes per magneto vs. 20 minutes with the static assembly process. The magneto assembly line demonstrated the basic principles behind continuous flow mass production, which quickly became known as Fordism: “Keep the work at the least waist high, so a man doesn’t have to stoop over; make the job simple, break it up into as many small operations as possible and have each man do only one, two or at the most three operations; arrange so the work will come to each man so that he shall not have to take more than one step either way, either to secure his work or release it; keep the line moving as fast as possible.”

It is easy to extrapolate how these fundamental processes can be scaled to encompass the entire manufacturing scheme. This would call for patient timing and rearrangement until the flow of parts and the speed and intervals along the assembly line meshed into a perfectly synchronized operation.

Once streamlined, engine assembly time was slashed from 594 minutes to 226 minutes. The moving assembly line allowed Model T production to climb sharply from 13,840 cars in 1909 to 230,788 units in 1914 to 585,388 units in 1916. As a result, retail prices dropped from $950 in 1909 to $490 in 1914 to $360 in 1916.

The millionth Model T was completed on Dec. 10, 1915. Five million had been completed on May 28, 1921. And by June 4, 1924, 10 million Model T’s had been assembled.

The introduction of the moving assembly line presaged the auto industry’s future, for with it came the realization that almost all movement through the factory could be mechanized and controlled by management. Ford Motor Co. was completely open about its new production methods and encouraged people to tour its facilities. Trade magazines such as American Machinist, Engineering, Iron Age and Machinery published extensive articles on the moving assembly lines and innovative material handling practices. In addition, Horace Arnold and Fay Faurote wrote a popular book entitled Ford Methods and the Ford Shops that detailed the entire Model T manufacturing process.

Due to Ford’s openness, production technology diffused rapidly throughout American manufacturing.

As in all endeavors across all disciplines, progress and innovation does not occur in a vacuum. One design or idea builds upon the predecessor. This is also the case with the modern assembly line. Legend has it, Mssrs Ford and Sorensen embarked on a trip to the north arctic in the late 1800s and were greatly inspired by what they saw…